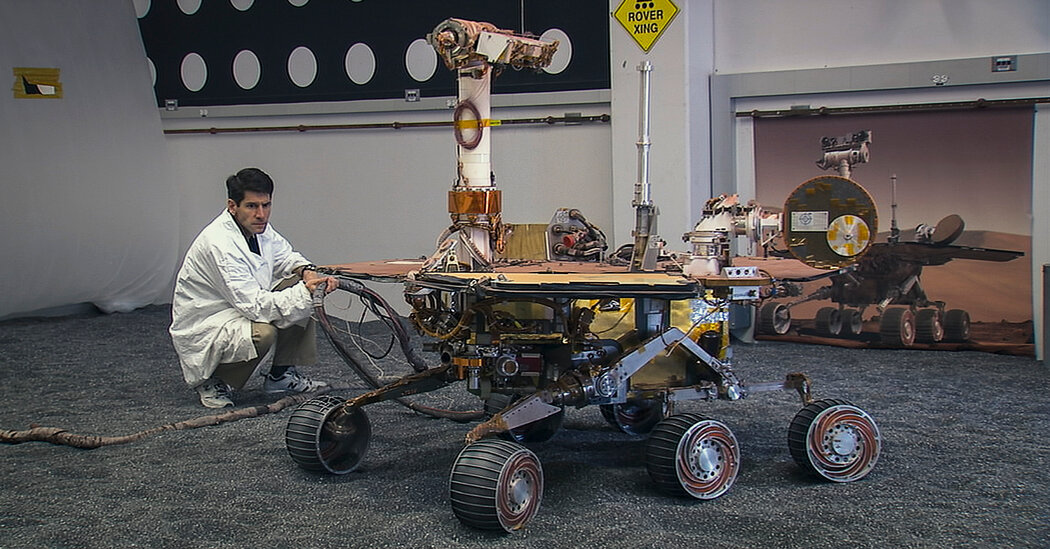

Early in the documentary “Good Night Oppy,” footage from late 2002 shows Steve Squyres, clad in scrubs, staring down in quiet awe, his eyes welling up as he shakes his head in disbelief. Squyres, the principal investigator for NASA’s first Mars rover mission, is watching his babies take their first steps.

That at least is the sense one gets from the improbably sentimental journey at the core of this movie (which begins streaming Wednesday on Amazon Prime Video) about the Mars exploration rovers Spirit and Opportunity (a.k.a. Oppy). Squyres vividly remembers experiencing this exact moment from the film.

“The first time it sort of came to life, it was a very, very moving experience,” he said recently over Zoom.

Squyres had long awaited the moment. A former geologist, he had worked on Mars exploration proposals for 10 years, including three failed submissions to NASA, before spending another six years, including three cancellations and revivals of the mission, building the machines.

As much as “Good Night Oppy” chronicles the depth of the human achievement behind the Mars rover mission — which was initially planned for a roughly 90-day stretch but instead lasted 15 years — the film is anchored most of all by a kind of pure devotion and connection to the rovers.

“We projected all of our hopes and our aspirations and our dreams into these machines,” Squyres said. “We built them so lovingly. You use a word like lovingly advisedly when you’re talking about a hunk of metal, but we put everything we had into those things.”

This is particularly evident in the film’s tense stretches in the control room after the rovers begin to encounter the trials of life on Mars. The director Ryan White and his team had free rein to sift through nearly 1,000 hours of footage, a good portion of which documented the mission’s tumultuous first 90 days, when cameras were constantly rolling. As the years went on, cameras were brought in primarily for emergency situations.

“NASA is smart enough and story-driven enough to know that they need to cover those beats, even if it’s not going to be immediately used,” White said over Zoom. “But the public was also along for this journey, so whenever Spirit or Opportunity was in a crisis, the public also felt like they were in a crisis. So NASA, from a PR perspective, needed to be covering that.”

While the movie rifles through this archival footage, the backbone of “Good Night Oppy” was built around a screenplay White wrote, a new concept for the longtime documentary filmmaker. He drafted a script based on dozens of preliminary interviews with the rover teams. Those early conversations, which occurred only a year or so after Oppy was officially declared dead in 2019, gave White the affecting sweep that would guide his film.

The interviews “were very therapeutic for people to get to return to that mission and get to talk about it,” White said. He used those talks as a guide to help imbue the film with the kinds of emotions expressed by the teams, aiming to make “far more than just a science film or an educational film,” he said.

The final component, though, that triggers the audience’s own visceral connection to Spirit and Oppy came from a collaboration with the visual effects company Industrial Light & Magic. The viewer’s glimpse of the rovers’ mission comes mostly through simulated sequences that were based on the rovers’ own photographs, satellite imagery of Mars and various data from NASA, which consulted on the process.

“From the very beginning the idea was, if we’re gonna do this, we want to put the audience on Mars in a way that’s never been done before in a film,” White said. The animated scenes were rendered to be cinematic and immersive, while also adhering precisely to the realities of the Martian terrain and geography.

The simulated rovers themselves, from their exact look to their movements and capabilities, were carefully designed to mirror Spirit and Oppy, while also lending them a humanlike air.

“‘Wall-E’ came up because it was such an endearing film about this little rover that’s trying to do stuff, so we kept that in our periphery,” Abishek Nair, one of the visual effects supervisors who guided the animation, said in a Zoom interview. “But at the same time we did not want to make it cartoony.”

The rovers’ real ability to toggle between filtered lenses, for instance, was animated to resemble blinking eyes. The result creates a strange bond that mirrored the experience for those at NASA.

Rover team members experienced the early days as “more of a mission,” White said. “The longer the robot survived,” he said, “the more that emotional attachment grew to them, where they were seeing a child or a living, breathing thing.”

Parents cried in screenings, White noted, seeing the rovers as a version of their children. For older viewers, it can be a moving story about aging and the gradual breakdown of a body.

Squyres remembered those final moments vividly. After Spirit died in 2011, the crew gathered for an Irish wake of sorts, drinking beer and reminiscing. “We were actually in pretty good spirits because we finished the party and then the next day we went back to work operating Opportunity,” he recalled.

Oppy’s death years later was different, though, bringing a true finality to the family that had formed around it. As the final wake-up song — a start-of-the-day tradition for the team chronicled in the film — Squyres chose Billie Holiday’s “I’ll Be Seeing You,” which looks back fondly on the end of a relationship, before one last failed attempt to make contact with Oppy.

“That was it,” Squyres said, still appearing emotional years later. “There was no party afterward.”