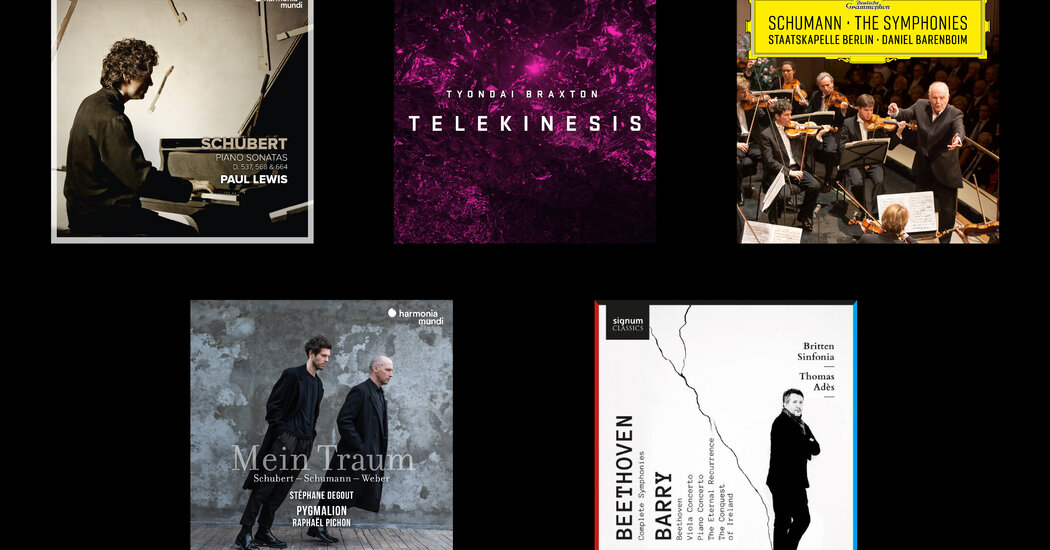

Schumann: The Symphonies

Staatskapelle Berlin; Daniel Barenboim, conductor (Deutsche Grammophon)

These recordings of Schumann’s four symphonies, made last year, are a glorious testament to the qualities that have made Daniel Barenboim, sadly now ailing, such an important, unique conductor for so long.

All the old Barenboim trademarks are present and correct in this, his third Schumann survey: an heirloom sound, the dark veins audible in the Staatskapelle Berlin’s chestnut strings; characterful playing, but only as far as is necessary to drive the symphonic argument; whole movements cast as single arcs, yet with such a natural ebb and flow within them; a sense of harmonic progress so sure that it is as if the conductor is lecturing you on the structure of the piece even as he gives it life. And, in three of the symphonies, there is also the inconsistency that is the unfortunate, inevitable corollary of the conductor’s thirst for spontaneity, though far less dramatically here than elsewhere in his discography.

But the Second! I cannot say that I have heard all of Barenboim’s many hundreds of recordings, but I would be astonished if this scorching performance did not rank among the finest of them. There is an electrifying, Beethoven-like impetuosity of development to it, but its intricate lines constantly sing out; the Staatskapelle’s musicians seem almost to be talking to one another, so communicative is their playing. Wilhelm Furtwängler, Barenboim’s lifelong idol, would surely be proud. DAVID ALLEN

Beethoven: Complete Symphonies & Barry: Selected Works

Britten Sinfonia; various soloists; Thomas Adès, conductor (Signum Classics)

There are institutions for which the recent Arts Council England funding allocation announcement this month was an existential shock. The 30-year-old Britten Sinfonia is one of them, having lost 100 percent of its support; in a statement, Meurig Bowen, the ensemble’s chief executive and artistic director, said, “For us, it was the guillotine, not the salami slicer.”

If any argument was needed for the orchestra’s artistic merit, it is in this Beethoven collection, which brings together previous volumes of a symphony cycle alongside works by the contemporary composer Gerald Barry, all conducted by Thomas Adès.

The Barry contributions can lean toward non sequitur, though sometimes land at just the right moment: “Beethoven,” a setting of the composer’s correspondence, echoes his orchestration; and “The Eternal Recurrence,” a setting of Nietzsche, follows Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” as if an answer. But the heart of this seven-hour set is the symphonies, which stand out in a crowded field for being so thoroughly, decisively opinionated.

You find yourself compelled by Adès even when not agreeing with him. Listeners may find the extreme attention to detail and texture in the early symphonies fussy. His “Pastoral” is more festive and balletic than serene. Harder to disagree with, though, is the impeccable balance throughout; the dignified restraint of his “Eroica”; the unruliness of his Seventh’s finale, exactly the bacchic romp on the verge of derailment that it should be.

Above all, this is Beethoven that lives. The instruments breathe and crunch. The scores reveal themselves anew. In the hands of these players, they still surprise, after 200 years. JOSHUA BARONE

‘Telekinesis’

Metropolis Ensemble; Brooklyn Youth Chorus; the Crossing; Tyondai Braxton; Andrew Cyr, conductor (New Amsterdam/Nonesuch)

I had been wondering what Tyondai Braxton was up to. This composer (and former frontman for the math-rock indie outfit Battles) hadn’t released an album since 2015. In the years since, he’s put out a few singles and an EP — all enjoyable. But fans of this electronic and orchestral specialist have been waiting for the next big statement. And here it is: “Telekinesis,” a 35-minute piece for 87 players (including the composer, on celesta).

The first movement, “TK1_Overshare,” shows Braxton in full command of his art: Regular low-brass eruptions propose a stuttering swagger alongside seesawing, Minimalist patterns in winds and strings. Brittle electric guitar picking pairs well with hollow percussive fillips. Various sections of the Metropolis Ensemble partake of brooding drone material. The conductor, Andrew Cyr, oversees some thick coloristic blends that muddy the boundary between acoustic and electronic. And that’s before Braxton adds in the singers of the Crossing and the Brooklyn Youth Chorus, during the second track, “TK2_Wavefolder.”

Each section of the score uses material heard during the opening, yet Braxton finds new ways to spin the material and keep things interesting. (The wigged-out electronics during the close of the third movement are a joy; ditto the churning strings and chorus of the fourth.). If “Telekinesis” never goes for the outright dance floor abandon of one of his electronic miniatures, like “Dia,” this work’s chiseled, insular quality proves plenty dynamic on its own obsessive terms. SETH COLTER WALLS

‘Mein Traum’

Judith Fa, Sabine Devieilhe, sopranos; Stéphane Degout, baritone; Ensemble Pygmalion; Raphaël Pichon, conductor (Harmonia Mundi)

Franz Schubert, master melodist and progenitor of the song cycle, never wrote for the theater with success, producing scores for singspiels, operas and incidental music that collect dust on the shelf.

With the new concept album “Mein Traum,” the conductor Raphaël Pichon, working with Ensemble Pygmalion, the baritone Stéphane Degout and the sopranos Judith Fa and Sabine Devieilhe, creates an operatic Schubert pastiche using found materials. Excerpts from his opera “Alfonso und Estrella,” the oratorio “Lazarus” and the “Unfinished” Symphony find new dimension alongside arias by Schumann and Weber.

A dreamlike narrative Schubert wrote down in 1822, one that sums up his song cycles with startling concision, provides the plot: “With a heart full of infinite love for those who spurned that love, I wandered.”

The album feels more like a ghostly mosaic or a mirage — evanescent, bewitching, fragmentary — than an exact telling of that story. For unity, Pichon organizes the program with an ear for instrumental timbres. Dusky horns flow from a Weber aria into the “Unfinished” Symphony’s Andante. Harrowing woodwinds wend throughout the album, and the pairing of bassoon and brass lends it a mournful glow.

The Pygmalion players, adroit in shifting styles, summon graciousness for Schubert and flair for the more theatrically astute composers. Degout, as the protagonist, sings with a vigorous, taut, darkly burnished tone. For her single assignment, Devieilhe somehow transforms Schubert’s overexposed “Ave Maria” into an aria of emotional, rather than spiritual, absolution — allowing the wanderer, finally, to rest. OUSSAMA ZAHR

Schubert: Piano Sonatas, D. 537, 568 & 664

Paul Lewis, piano (Harmonia Mundi)

“The music is at its most powerful when you allow it to speak for itself,” the British pianist Paul Lewis told The New York Times this year. He was speaking about late Brahms, but that idea could almost stand as a maxim for Lewis’s artistry as a whole. His interpretation of the Viennese Classical and early Romantic tradition — often so nuanced and understated that it hardly seems like interpretation at all — has made him one of the most admired pianists in this repertoire.

Nowhere have his efforts been more successful than in the music of Schubert. Having already set down first-rate recordings of this composer’s later sonatas, he turns here to three comparatively youthful works, for an artist who died at 31. Sunny, Mozartean lyricism dominates the sonatas in A (D. 664) and E flat (D. 568), seesawing turbulence and repose in the A minor (D. 537).

Yet even in these relatively early works there are occasional glimpses into the darkness that would nearly engulf Schubert’s music later on. Lewis renders everything with his now-familiar immaculate tone and elegant phrasing. His disinclination to push and pull at tempo or dynamics means that when moments of crisis arrive — as in the first-movement development of the D. 664 Sonata — they carry outsize force. It takes considerable skill to make music this emotionally charged sound so natural and unaffected. DAVID WEININGER